PROUD MEMORIES OF DAD...

AND A

HISTORIC EVENT

by Kate Hofstetter

Nine year old Bruce Reichelderfer

watched from his front porch with awe

and admiration, as the huge, beautiful

ship prepared to moor at the Naval

base in Lakehurst, New Jersey. His

dad, Francis W Reichelderfer, executive

officer of the base, was packing and

would leave with the other passengers

and crew when the ship deported the

next morning for Frankfurt, Germany.

As the vessel approached, Bruce

was filled with a sense of pride. He’d

been aboard her with his father just

days earlier when the captain gave

officers on the base a courtesy cruise.

The ship was beautiful inside, Bruce

remembers. There was a dining room

with windows that gave you a panoramic

view of the harbor and a lounge where

adults could go for a drink. There

were 72 sleeping berths and even a

dance hall. It was German-built and an

impressive sight as he gazed upward at

its huge body. He longed to go with his

father.

The shipwas built in Friedrichshafen,

Germany and Bruce knew it was over

800 feet long and 130 feet in diameter.

He’d seen it with his dad when it

was just a huge skeleton, still under

construction.

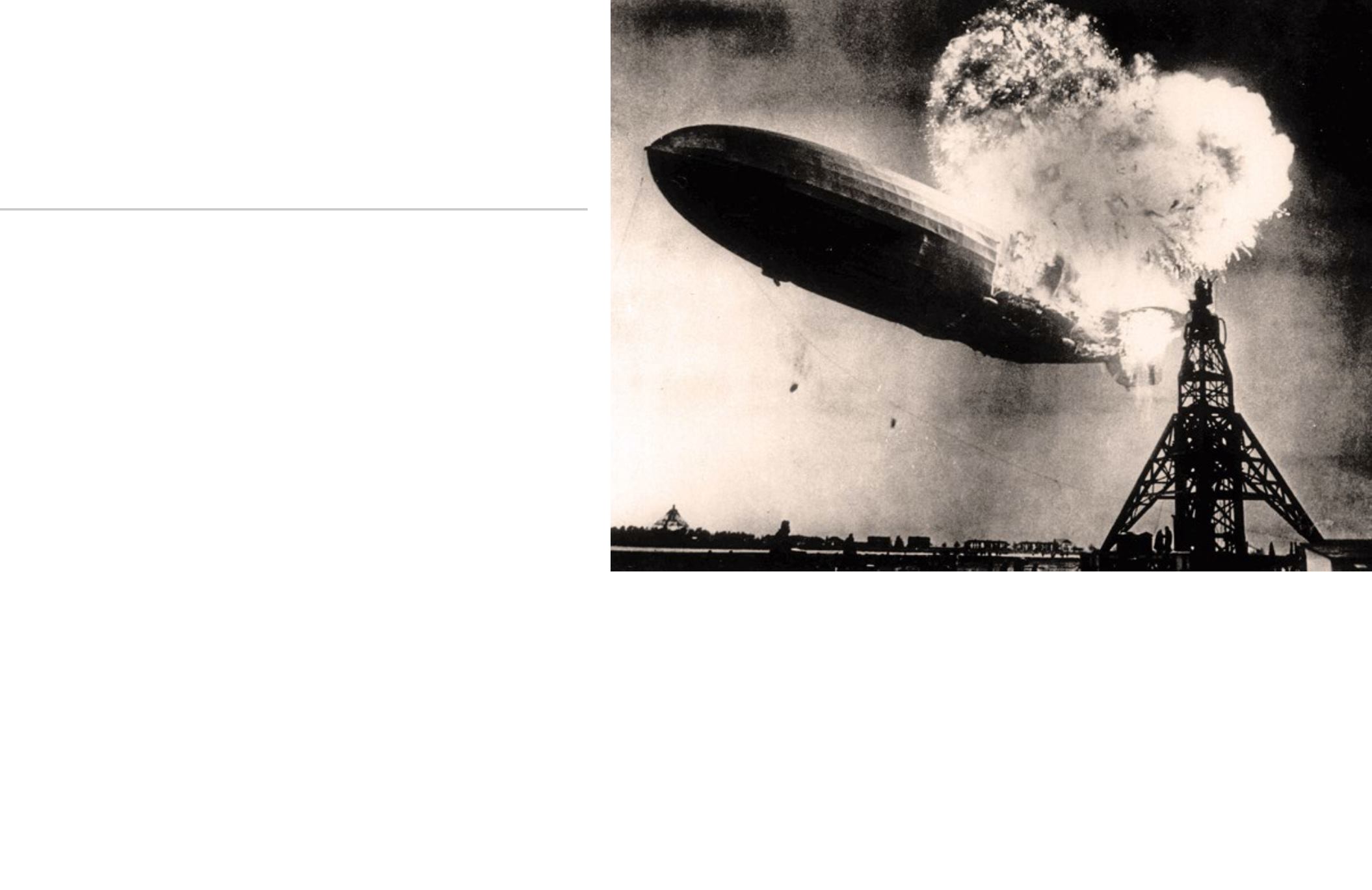

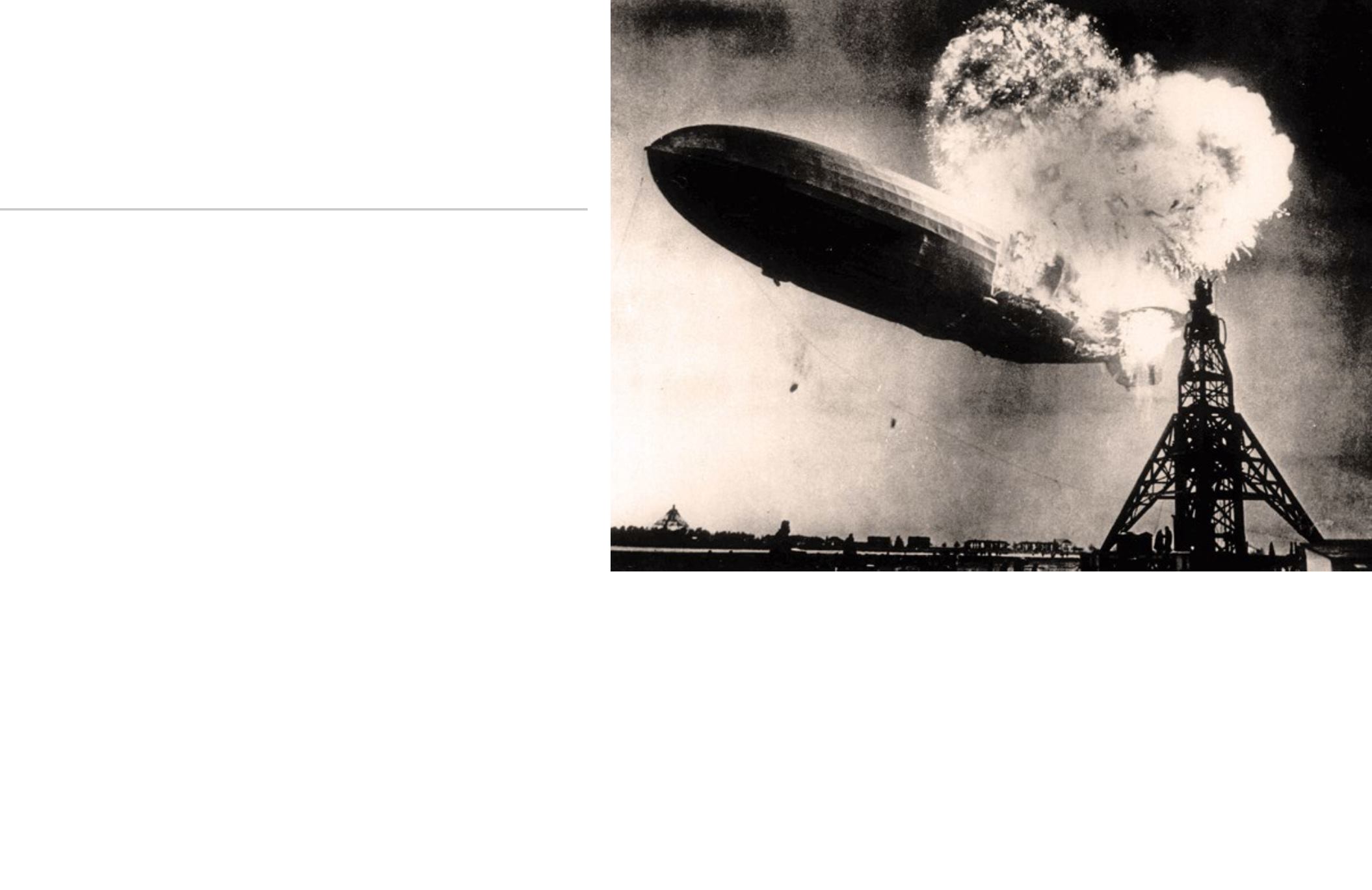

Then he saw something he will never

forget. “It was a ball of fire,” he says ,

“just forward of the upper fin.” The fins

were near the rear of the ship. Next

came the glow of flames. He whirled on

his heels and ran to tell his father. The

Hindenburg

was on fire.

It was the evening of May 6, 1937.

As a ground crew waited to catch the

landing lines and anchor the airship, a

thunderstorm and shifting winds kept

the captain from docking on his first

attempt. Instead, he circled the base

and waited for the storm to subside.

On the second approach, he gave

the vessel full rudder as he went into

a series of turns, fighting the wind.

Although what exactly happened to

cause the

Hindenburg

to burst into

flames is still a mystery, most experts

today believe the hard turns the captain

made stressed the ship and may have

snapped a cable which allowed leakage

of hydrogen gas. They believe the ship

had picked up static electricity from the

surrounding thunderstorms.

Bruce is sure of what he saw. “It was

a ball of fire about 3 feet across,” he

says, “and the only thing that comes to

mind to describe it is St Elmo’s fire.”

St Elmo’s fire is a weather

phenomenon that often occurred on

the masts of ships or the wings of

planes during electrical storms. At first

glance, St Elmo’s fire appears to be

blue flames or a violet glow. It is not

actually fire and it has been mistaken

for ball lightening. Often accompanying

the glow is a distinct hissing or buzzing

sound. It can appear on leaves, grass

and even the tips of cattle horns.

According to an Online

encyclopedia, it is the

electric field surrounding

the object in question (in

this case the

Hindenburg

)

that causes ionization of

the air molecules. Roughly,

1000 volts per centimeter

induces St Elmo’s fire. The

mixture of nitrogen and

oxygen in our atmosphere

creates the glow, much

like a neon light.

Certainly,

with

an

electrical charge and a

hydrogen leak you could

expect disaster. Bruce

believes the wet landing

cables did not help

either, as they provided

a ground to complete the

electrical circuit. Cables,

he explained, were lowered from the

hull of the airship to a ground crew in

what was called a “high landing”. The

cable was then tethered to a winch

and the ship was lowered mechanically

from the ground. There is no doubt in

his mind that the storm was the culprit

in the tragedy that occurred that day

within view of his family’s quarters.

There were 97 people on board the

Hindenburg

when it was destroyed by

fire and 62 survived. Of course, there

were many serious injuries among the

survivors. Bruce remembers seeing

people jump from the wreckage to

escape burning to death.

“They landed on ballasts that had

fallen through the hull,” he said, “and

that cushioned their fall and saved

their lives.”

The ballasts, he explained were

filled with hundreds of gallons of water

and were used to trim the ship. In fact,

that eventful day in May three ballasts

were jettisoned in an attempt to take

weight off the rear of the vessel. The

captain had also ordered several crew

members to the nose of the airship to

redistribute weight as the nose of the

ship kept drifting upward. All those in

the nose of the aircraft perished in the

flames that day.

Dirigibles were a novel idea and

an engineering fete worth saluting,

however, what happened to the

Hindenburg

ended the era of “lighter-

than-air” ships. They were just too

sensitive to weather conditions. The

Hindenburg

was only one of several

disasters involving this type aircraft.

However, Bruce, like his father,

has been fascinated by these airships

all his life. The lighter-than-air craft or

dirigibles, are powered and steerable

(as opposed to balloons) and they

include three classifications: blimp,

such as the one owned by

Good Year

;

semi-rigid like the

Zeppelin

and rigid like

the

Hindenburg

. The shape of a blimp

is maintained by gas, such as helium.

The shape of the rigid

Hindenburg

was because of a full metal framework

while the semi-rigid craft typically has a

metal support that runs from the nose

to the tail internally.

Bruce’s fascination with dirigibles

was passed on to him by his father,

who was one of the few Americans ever

licensed to fly lighter-than-air craft. In

Discover Smith Mountain Lake

Fall 2013

39

38